|

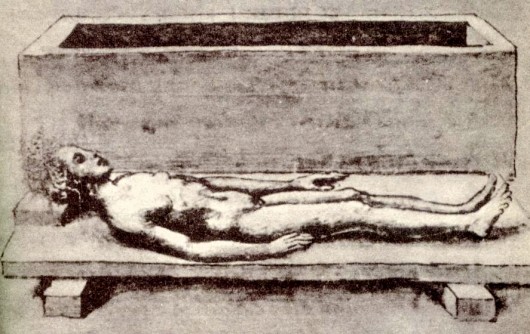

| Helena Rosa Wright |

From a rather interesting article by Paul Spicer at the Mail Online with the headline of "Desperate wives and the man known as Derek who fathered 500 children with women whose war hero husbands were too shell-shocked to make love" :

These days there are sophisticated and scientific solutions to the dismal problem of childlessness — IVF, Viagra and well-established egg and sperm donor services. We think of these as recent advantages and give thanks for the modern age.

But what only very few people are aware of is that long before sperm donation was practically or ethically possible, in the early 20th century a secret sperm donation service existed for those women most in need.

Helena Wright was a renowned doctor, best-selling author, campaigner and educator who overcame the establishment to pioneer contraceptive medicine in England and throughout the world. Kind, intelligent, funny and attractive, Helena had a way with words and a devoted set of friends. She adored men and spent her life helping women.

She had a great hit in America and Europe with a book called The Sex Factor In Marriage, which financed her innovative medical practice. She opened two London clinics: one for very privileged women in Knightsbridge, one for the poor in Notting Hill.

And it was from these offices that she undertook perhaps her greatest work: to assist hundreds of women whose husbands had returned from World War I unable to father children.

And this from

the Spectator with its headline "

A secret sperm donor service in post-first world war London":

Between 1914 and 1918 one million Englishmen were killed in France and Belgium. Thousands more were wounded, gassed or shellshocked in the trenches. The appalling losses of the war left many women widowed and led to a shortage of potential husbands, a gender imbalance compounded by the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918. They were known as ‘the mateless multitude’.

Among the men lucky enough to return home to wives after the war, many were un-able to perform sexually, whether because of direct injury or shellshock — what we’d call post-traumatic stress disorder. It was a tremendously delicate subject — witness D.H. Lawrence’s decision to make Clifford Chatterley ‘only half a man’, deprived of his virility by war; this aspect of the novel was considered to be the cruel breaking of a taboo.

No wonder, then, that by 1918 Helena Wright had many hundreds of women on her books who had confided to her that they needed help. These women loved their husbands and would never have left them, but they also craved children. What they needed was a sperm donor, before such a thing existed.

More on Helen Wright:

Further Reading:

"Freedom to choose: the life and work of Dr. Helena Wright, pioneer of contraception" by Dr Barbara Evans