Queen Helena of Adiabene lived in the first century C.E. in the semi-autonomous kingdom of Adiabene in the upper Tigris region of Assyria. She famously converted to Judaism and spent many years in Jerusalem—where her generosity and piety earned her a lasting legacy.

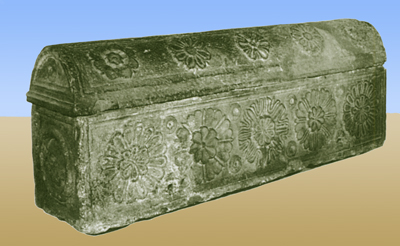

Louis Félicien de Saulcy excavated the Tomb of the Kings—really the tomb of Queen Helena of Adiabene—in Jerusalem in 1863. He discovered five sarcophagi in the tomb, as well as a broken sarcophagus lid.

Essentially, the only line of argument for the identification of the sarcophagus with Helena is (a) Queen Helena of Adiabene was buried in one of the chambers in the tomb, and (b) the woman buried in the inscribed sarcophagus is called “queen.”

Who Was Queen Helena?

Helena of Adiabene was queen of Adiabene (a Persian province on the northern Tigris and vassal kingdom of the Partihian Empire) and sister-wife of Monobaz Bazaeus I (source: Josephus .

Jewish Antiquities xx. 4, § 3;). With her husband she was the mother of Izates II and Monobaz II. She was possibly Zoroastrian prior to her conversion to Judaism c.30CE.

Helene played an important role in the succession of her son, summoning the nobles of the kingdom and informing them that it had been her husband’s wish to nominate Izates king. Declining their advice to put Izates’s brothers to death in order to avoid plots against him, she instead placed her elder son, Monobazus, as guardian of the country until the return of the heir. Josephus lauds her for all these sage decisions. On Izates’s death in 55CE, she returned to Adiabene to see her elder son Monobazus crowned king.

The Talmud speaks of important presents which the queen gave to the Temple at Jerusalem which included a golden candlestick (sometimes called a lantern) and golden plate (also referred to as a plaque); she was also generous with gifts to aid the famine stricken city of Jerusalem in 46–4CE.

She died shortly after the coronation of Monobazus c.56CE, having moved to Jerusalem. The bodies of both Helene and Izates were then buried in the royal sepulchre (pyramidal tomb) she had built while in the city. These tombs are now said to be located in the catacombs known as the "Tomb of the Kings", said discovered in the 19th century by Louis Felicien de Saulcy.

See Also: